|

Late in Term 4, most schools have a morning or day where the children visit their new teacher, classroom and and classmates for the following year. Today I wanted to share some tips with you on writing a letter / e mail or planning discussion points to share with your child's new teacher before they meet your child. This is not intended to cover introducing your child to their new teacher for next year if they are starting kindy, reception or changing schools partway through their schooling. Those events require more planning, meetings and lead up to transition visits than I can cover in this blog post, however you may get a few useful hints to use in that process. This is purely for change of classroom teacher from Reception to Year 1 and so on, where the teacher will already be vaguely aware of your child's additional needs and been briefed by their current teacher.

It is best to explain SM and how to approach a child with SM BEFORE the teacher meets your child. The first meeting is really important and can set the tone for all future interactions. Lots of parents and teachers forget to prepare the new teacher before Moving Up Morning / Transition Visits and leave it all until late January, the first day of term or worse still until week 2/3 of term 1 to allow the child to 'settle in to the new class first'. Please don't! Those are 2-3 weeks where the teacher is likely to be unwittingly asking your child questions, pressuring him/her to speak and not doing all the things which could make the transition so much easier. It is not their fault if you don't educate them. The other mistake that some parents make is coming on too strong too soon. It is Term 4; the children are exhausted, the parents are exhausted, the teachers are exhausted and they are busy with end of year reports and class events. They do not have the time to get deeply involved in the ins and outs of SM right now. All you should be looking to do is give the teacher the information they need to make your child feel comfortable at Moving Up Morning, introducing yourself and opening up a dialogue with the new teacher. Keep it simple! After Moving Up Morning, I suggest that you send a second e mail thanking them for taking the time to make your child feel comfortable and asking if would be possible to get in contact when they are back at school setting up the classroom in January. Once they have recharged and they are back at work, then you can arrange to send them more detailed info on SM, meet up in person and also arrange a visit for your child to see their new classroom and have some 1:1 time with the teacher before the start of term. Handling this meeting is a separate blog post / book chapter which I can't cover now. Here is a copy of one of the many letters I have sent to teachers before Moving Up Morning which you could use as a template and adapt to your own child's stage of recovery. This one was for a child moving up to Year 2 who was already verbal with current teacher but only in certain situations. Info for Mr. Teacher on Selective Mutism re: Pupil P Hi Mr Teacher, Thanks for taking the time to read this info about P and Selective Mutism before Moving Up Morning. SM is a treatable anxiety-based disorder where children have an extreme fear of speaking in social situations outside the immediate family. For more information on SM see www.selectivemutism.org. The fear of speaking is so real and strong for these children that there have been cases of SM kids with broken limbs unable to ask for help. P's best friend is child A. She can also talk to child B and C. I have asked Mrs. Teacher to pair her up with child A on the walk over to your classroom next week as this will help to lower her anxiety levels. If the children will be allowed to choose a seat it would be wonderful if you could ensure that she is close to her friends. At moving up morning, there is no need to try too hard to make a big effort with her, in fact that is counter productive. As long as she is doing fun activities that don’t require speech and is with her good friends, she will be fine. You can say hello and be friendly, make nice comments about her work but avoid asking any questions. The main thing to remember is that it is an ANXIETY disorder and NOT a speech disorder. Therefore the goal of treatment is to reduce her anxiety by removing ALL PRESSURE on her to talk. This means:

The new children in the class will soon notice that P is shy and quiet. In The Selective Mutism Resource Manual the authors suggest that if children start commenting on a child’s shyness or lack of speech it is best to play this down straight away with a response like: ‘P can speak perfectly well in her old class / at home and lots of children take a while to warm up. P will soon be able to join in when she is used to us all.’ It’s unlikely for P to relax enough in the short time the class is together on Thursday morning to start to make new friends. My main concern is for her to just register the different faces, room and teacher; for her to realise that lots of her classmates will still be with her and that lots of things are still the same. I’m more concerned that there is as little stress and challenge as possible at the Moving Up Morning than that she makes friends, so that her anxiety levels are low when she thinks about her new class during the holidays and develops a positive association with the new situation. Thanks for taking the time to read this and I look forward to working with you. Kind regards, Susannah Bryant Sometime in summer 2016/2017, I was invited to be a guest on Clare Crew's Thriving Children Podcast. Clare is a Mum, teacher, professional speaker and passionate advocate for helping children to reach their full potential through movement, play and connection. Clare herself had a form of SM as a child and is also a parent to a child in recovery from SM, so we had lots to talk about!

Here is the link to the episode I featured in. Skip to 01.35 to miss the Wellness Couch Promo section. https://thrivingchildren.com.au/episode-51-selective-mutism/ There are over 100 more episodes to enjoy from Clare's Podcast which is available free on iTunes. I was also a guest on the written blog. Here is the link to that article: https://thrivingchildren.com.au/selective-mutism/ Over time, I'll put up some more media links that I have found particularly useful. A question that I’ve noticed coming up fairly often in the SM facebook groups I’m part of, relates to how to help your child when meeting new people in public such as shop assistants, doctors, bus drivers, child’s friends’ parents. I often want to reply to these giving tips but don’t always have time, so thought I’d do a generic article here that I can refer people to. I actually started out writing a blog post for all of the above scenarios, but it was too long. So today I’ve broken it down into this one subcategory of interactions. The way you help you child to interact with adults who s/he is not likely to ever meet again, or form an ongoing relationship with is different to the way you approach their relationship with their friend’s Mum, their GP or dentist for example. These tips are for brief interactions of a few minutes (such as retail, hospitality staff, friendly people you meet at the park) …… not extended interactions, even if they are a one-off (such as seeing a different doctor to usual or having a hearing test with an audiologist or nurse). Set goals in advance with your child You might say something like ‘You have been doing so well with waving bye at the shops lately. Do you think today you would be brave enough to tap Daddy’s credit card at the check out today?’. Summarise what they can already do and negotiate on an appropriate next step, plus what the reward will be, if there will be one. Have a repertoire of set positive phrases you can use When you are meeting people briefly, then there is no time to explain SM to them and this would probably be quite negative for your child if everywhere you go you are drawing attention to the problem during the exact thing that they are anxious about – interacting with new people. If you are constantly going on about SM then they can internalise that and it becomes such a huge part of their self-image that they can see it as a fixed part of their personality that will never change rather than a temporary problem, which can be overcome. It also doesn’t help to dumb down SM to make it easy for people to understand in a brief interaction, by labelling the child as ‘shy’. Again, shyness is a personality trait, not an anxiety disorder and can be confusing to the child if they internalise it. It is best to use the same positive language in front of the child, when speaking for the child and when explaining the child’s behaviour, as you would use with the child in goal setting at home; so instead of focusing on the problem, focus on the solution. “Josh is working on his brave talking.” For example, if a shop assistant says to your child: ‘Hello, how old are you?’ and you know it is unlikely s/he will be able to respond, then here are a series of steps you can use to keep it positiveand take into account some of the important steps listed later on (take control when required, prompt the child to do something achievable, protect the child): 1. Don’t rescue the child too soon. Wait 5-10 seconds – although it is unlikely that your child will answer, stranger things have happened, allow time for the child to respond in some way. This is a very uncomfortable moment for the other person, for you and for the child. However it is important for you both to work on increasing your ‘distress tolerance’. This may be that special moment where they nod or shake their head for the first time in response to a yes/no question! Sometimes the other person will be so uncomfortable during the silence that they will start to ask more questions, in which case skip straight to Step 2. 2. Use your set phrase. ‘Skye is still working on brave talking with new people.’ Other examples of set positive phrases include statements about what your child is working on. These act as a clear message to the other person not to expect more than this and not to push for more. E.g. ‘Max is working up to talking to new people. We are going to start practising waving hello / smiling / nodding soon’. At that point you may not be offering an alternative way to answer their question, just showing that the child will not be answering, that you are aware that this is unusual and the situation is being dealt with. 3. Prompt the child to complete an alternative action that is achievable for them, if appropriate and possible. This needs to be age and stage of recovery appropriate and be something that they are expecting, working on and being rewarded for. It might be holding up their fingers to show their age, or nodding when you get to the right age. You would usually need to take over the interaction and be a kind of translator for your child. So after your set phrase you might repeat the question yourself: ‘Skye how old are you? Can you show Mummy how old you are on your fingers? Yes, you are four. ‘It can help to slightly turn away from the person and create a bit of a barrier with your body so the child’s response cannot be seen by the stranger. Then you turn back to the assistant and say ‘She is four’. 4. End the interaction on a positive note if possible and protect the child if necessary. Once your child has completed the alternative action, try to signal to the other person and to the child, that this is the end of the interaction (unless they are further down the track of recovery and then if the interaction is going well, you may want it to continue). That way, the other person doesn’t continue to ask more questions where you may not have an achievable alternative option for them. In other words, quit while you’re ahead! It may be something like giving the child a job to do such as loading the shopping, giving them 20c to put in the guide dog collection, giving them an apple to eat, reminding them to ‘be quick because we need to get back in time for….’ or asking the other person how their day has been to distract them from continuing to focus on the child. If the interaction was not successful then finish up with a quick: ‘Well done for trying, we can practice again another day’. 5. Reward the small steps. After the interaction (usually once away from the person), most children like a verbal acknowledgement of their achievement. I’ve talked before about how / when to reward and will again but I can’t cover that here as it would be too long. Some children love effusive praise for their achievements immediately after, others find it extremely embarrassing and don’t even want it mentioned. For those children, it may be best to not mention anything until a couple of hours later and then in a businesslike way just say ‘We’d better put that sticker on your chart for waving bye to the lady in the pet shop before we forget’ or even just putting the sticker on yourself and write underneath ‘waved bye at pet shop’, casually telling your child that you put their sticker on and that they have X number of stickers to go until they get their Sylvanian Families Bathtub & toilet set. These children may appear as if they have no interest in the sticker chart until they get the end reward but are often secretly proud of what they have done. N.B. Young children will require an immediate reward and may not be able to relate that the sticker they will get will ultimately lead to something bigger. Keeping some sparkly stickers in your purse to give to your child IMMEADIATELY after the interaction is good here, and/or you can keep something non-perishable in the car if a physical reward is required e.g. Snake lollies cut up into little pieces in a jar in the glove compartment. **As a side note, if you do not believe in using rewards / sticker charts in parenting, I share your concerns, but when a child has an anxiety disorder, we are asking them to do something which is terrifying for them. They are not going to be intrinsically motivated to change, the whole disorder is about avoidance, so bribery and corruption are really useful. The intrinsic motivation comes later on in treatment. I believe I talked about this in more detail when I was a guest on the Thriving Children Podcast. I should put the link up to that sometime…. It’s also not appropriate to use foods as a reward for children in most situations, but it is warranted sometimes when treating SM. I don’t mean handing your child a chocolate bar every time they high five their swimming instructor, more like giving them one cube of chocolate (as well as their sticker towards new toy/book) for any big firsts. If you are family who avoid sugary foods, all the better, as these items are an even bigger treat and carry a higher perceived value to your child. Again, I share your concerns, we are a minimal sugar household, but a few Freddo frogs are not going to damage your child’s health as much as an unresolved anxiety disorder – needs must! I think I need to do a entire blog post on this….** Set the example Social anxiety is the most heritable of anxiety types, so if you have a child with SM it’s not unlikely that you also suffer with some anxiety yourself, social or otherwise, and this can make these awkward interactions with strangers all the more stressful for you as you really identify with what your child is going through and are also anxious about what any onlookers are thinking of you, your child or your parenting skills. If you are not someone who likes to make conversation with strangers, you may need to set yourself the challenge of increasing your friendly communication with new people in as many situations as possible to model to your child that it is possible to enjoy meeting new people. If your social anxiety affects you significantly, then getting treatment yourself is also going to help your child. Even if you are not an anxious person, supporting your child with SM is a big strain and can bring on some anxiety, especially in these situations where your brain has learned to anticipate stress, embarrassment and worry about your child. Unfortunately, children pick up on EVERYTHING! So I’m afraid you are going to have to fake it til you make it. Try to project an outward aura of calm, assertiveness and approachability. Use deep breaths, grounding exercises, power poses, whatever you have to, to get through these experiences. It is also okay to acknowledge to your child if you struggle with the same things that they do, but make sure you show them a growth mindset and not avoidant patterns of behaviour. They need to see that Mummy or Daddy get scared too, but that they are brave and will do it anyway until it gets easier. You also need to model assertive behaviour for your child. Practising in advance and brainstorming ideas with your partner, friend or psychologist may help with this and with the next suggestion, which is…. Don’t be afraid to take control when required It’s okay to take over and drive the conversation to engineer opportunities for success for your child. It doesn’t matter if you seem a bit weird to the other person. Maybe the stranger has asked your child’s name, they did not answer and you have used your ‘set positive phrase’ (which includes the child’s name and therefore answers the question) but maybe you follow up with your own question that you know / hope they can answer. Pre-empting the next likely question and asking it yourself gives your child the chance to practice answering you in front of the other person, if they can’t answer the person themselves, even if it is just with a barely audible whisper, an almost imperceptible nod or a smile. You can usually guess what people are going to ask; with little kids, people usually follow a format – name, age, what did you do today, question about something they are carrying / wearing / eating e.g. I like your T shirt / do you like Peppa Pig? / That looks like a yummy banana / Is that your baby brother? What’s his name? / Would you like a sticker? / Would you like a balloon? Are you allowed a ….? Set them up for success Don’t set your child new challenges when they are tired, hungry, unwell, or particularly anxious. Don’t prompt them to interact with someone who looks like just the kind of person who will trigger their SM. Let them hide behind you this time. If they’re in a great mood and pumped to try something new and then they fall over right before, take a break to fully recover before you attempt it. Going through the check out and they are all set to try to ‘wave Bye’ for the first time? Choose your lane carefully. Look for someone who looks gentle and approachable. Try new things when they are on a natural high after confidence boosting and anxiety-calming exercise. Keep goals age and stage appropriate You can’t just go from diagnosis in a young child, to setting a goal of waving to the check out guys. A newly diagnosed three year old with moderate to severe Selective Mutism is likely to still be clinging to your leg every time you leave the house or hiding under tables at birthday parties (if they can even be persuaded to go at all). Waving hello to the host of a party or making eye contact with the guy on the check out may be simply too big of an ask. Work out where they are now and set a goal that is achievable for them. It might be something as simple as “When we are the shops you need to practice being brave by letting go of Daddy’s leg. You need to walk next to me and hold my hand.” In a child with super high anxiety, it may be appropriate to shield them from interactions with strangers and talk for them whilst whatever you are doing to lower their anxiety in the initial phase after diagnosis takes effect. You might set the goal of them walking beside you through the supermarket aisles but allow them to hide behind you at the checkout, or use your body as a barrier to discourage the checkout person from initiating conversation. If however, they are at the stage of whispering a few words to their teacher when no one else is listening and talking to one or two friends out loud in the playground; then it is not appropriate to avoid taking them to places and putting them in situations where people will ask them questions. Protect the child from people who come on too strong or who are negative / shaming Some people mean well but are just insensitive or have poor social skills and may not pick up on or accept your cues that you do not wish your child to engage in a social interaction with them. You don’t know what is going on in people’s lives. The person who wants to pursue the contact may be very lonely and be delighted to have the chance to speak to people when out and about. A lot of people just really love kids. This is a particular problem of middle aged women who are parents of grown up / teenage children….they think they know how to relate to all children, they miss the time when their kids were little, aren’t yet a grandparent and can take ‘getting this 3 year old kid whose Mum says he doesn’t talk to strangers, to open up to me’ as some kind of personal challenge, either that, or they like to give you lots of advice on how best to deal with the situation! You also need a back up plan to deal with idiots. These are the kind of people who in spite of you using your ‘set positive phrases’ don’t take the massive hint that this child has a diagnosis and think that your child is rude, ill disciplined and that you are basically a rubbish parent. You cannot win with these people. The best thing to do is get as far away from them as quickly as possible. It is extremely upsetting to be judged like that, but you need to put on a brave face for your child and talk to another adult about it later or have a cry when they are not looking. Your child is already fearful of strangers and having attention drawn to their not speaking. Then a stranger starts to judge them, or tries to force them to speak. If that stranger judges their parent, and is in a negative interaction with their parent then that is like their worst nightmare. If you react strongly and give that person a piece of your mind, it is just going to add to the stress for your child. You need to end the interaction in a calm and assertive way that lays down boundaries and shows your child that you will protect them. This is where having some one-line retorts come in really useful, start out gently and gradually increase the severity. Some ideas of things you could say include:

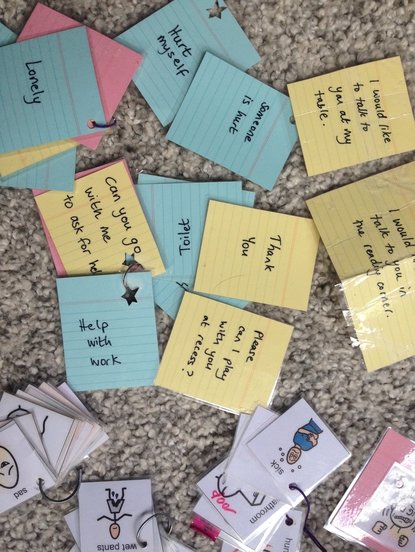

With very young children, you can use deliberately complex words quite quickly and quietly so that they don’t really hear or understand what you are saying such as ‘I don’t appreciate your interference, there is a medical diagnosis in our situation.’ If the stranger does not react to the word diagnosis or anxiety, then they are just not going to get it. More often than not when you come across an idiot their judgements will be non-verbal or passive-aggressive, such as sighing loudly, tutting, staring or commenting to their friend just loud enough so you can hear. Hopefully, a young child will not notice or can be easily distracted, so it is best not to engage with these people so that your child continues to be blissfully unaware. Remember that it does not matter what the stranger thinks of you, or your child, it only matters that child does not become even more fearful of social situations. It does not matter if the stranger makes any kind of unfounded assumption about your child or your family. It does not matter if they feel like they have ‘won’ because you did not react. It only matters that you can make your child feel safe and protected in that situation. Luckily these people are few and far between, but being prepared with a quick response can shut them down rapidly and defuse the situation before it damages your child’s confidence. Be prepared to walk away, even if it inconveniences you significantly, e.g. walking out of doctor’s waiting room “to go to the toilet” (risking being called while you are gone) if another waiting patient is commenting on your child. You are more likely to get a reaction from this kind of idiot if your child externalises their anxiety with bad behaviour. Most SM kids are too anxious to externalise their anxiety through acting out, but I have had one of my girls be like this when she was 2-4 years old, whilst she was a bit young to have insight into her own anxiety and particularly before we knew what was wrong, as we inadvertently made things worse! I know that it is hard, but try to keep your response to your child consistent with what you would do if no one were watching. Don’t change your response to placate other people. Zone out other people and try to respond in the moment. Your parenting is the sum total of a lifetime’s work and is not encapsulated in this one moment. Manners do cost something Just a reminder…the words please, thank you, hello and goodbye can be extremely difficult for kids with SM, even once they become verbal. By the time they are diagnosed they have been pressured hundreds or even thousands of times by their parents and other adults to ‘say please and thank you’. Even where everyone is quite sensitive to the fact that it is normal for young children to be shy around strangers, we do tend to think that they should at least say Hello, Goodbye, Please and Thank You. Other people also often think this; they might say: ‘Are you shy? That’s okay, I was shy when I was your age, you’re only little!’ and then two minutes later say ‘What do you say? Mind your manners!’ when they give the child something and don’t get a ‘Thank You’. This is an awkward moment for everyone because the social contract of basic politeness has been broken. I find that when your child has perhaps said a word or two or has had some kind of non-verbal interaction with a person but can’t manage to say thank- you or goodbye, a pre-emptive strike is helpful. I would personally be effusive in my thanks to the person to show that I have manners and am modelling manners to my child, I would also reply on behalf of my child ‘WE really appreciate, don’t we?’ Big smiles from you go a long way. They might be at the stage where you can say ‘Give the lady a big smile to say thank you for the balloon’ or ‘Can you do a little wave to say thank you and goodbye?’ or ‘Give the man a thumbs up to say thanks’ or ‘Can you whisper thank you in Mummy’s ear?’ and then saying ‘Well done! She says thank you’ (even if she just made a tiny noise in your ear). You know your child best and will work out over time which things are harder for them. For some kids it is the eye contact, so they might do a halfhearted wave without looking at the person. That is okay, at least they waved, praise that! When waving is easy and routine, then work on the eye contact. Maybe the word bye will come before the eye contact; whatever order it happens in is okay. Other children hate making gestures or signs. They might give a lovely smile but not be able to wave goodbye. You have to be flexible and adapt to suit your child’s strengths, weaknesses and triggers. The use of help cards for children with SM can be controversial as some feel that it is enabling the child to continue avoiding speech. From my perspective I find them very useful in lowering the child's anxiety about things that may happen as a result of their inability to communicate their needs. E.g. not having to worry that they will wet themselves because they can't ask to go to the toilet. Cards are therefore a temporary accomodation. Here's how you use them and as a bridge to speech rather than an enabling thing:

1. For children who can't yet read well- use cards with pictures or symbols on them as well as one simple word. You need things like: toilet, hungry, thirsty, sad, wet pants, tired etc. 2. Make several sets of help cards as they will lose them. They are best off laminated and kept on a ring. You can keep a set in their drawer, in their bag, give one to the teacher, give one to each specialist subject teacher if they have them. Then they can also keep a set in their pocket or on a lanyard if they are comfortable with that. The other option for really little ones who perhaps don't have the patience to leaf through cards is a laminated board with all options on and the child can point to the need or state. 3. How will they get the teacher's attention to show the cards? They may not be brave enough to queue up to show the cards. Ask the child what they would be comfortable with. Maybe a sign or asking a friend to go with them. Hopefully the teacher is sensitive enough to notice and approach the child first. Once that becomes easy you can then continually set and reward new goals e.g. putting up your hand for help, queuing up for help. 4. Each time they take a first big step I find it easier if the parent or support person is there to nudge them along. You can rehearse in advance : 'Ok so today we are going to use your cards with Mrs Wilson. I will go with you and queue up to show her your toilet card when you need to go. Then you will get 4 stickers on your chart and a chocolate frog when I pick you up!'. Then stay and practice the new thing several times, giving a sticker for each repetition. Don't expect them to be able to practice once with you and then that's it. Continue to reward them heavily the first few times they initiate use of the cards themselves. Then 1 sticker for each use. Each time you up the difficulty level, go back to heavy rewards for the first few times. 5. As soon as the child can read well enough, make the cards more complex so that their needs are better met and they can express themselves more fully. We've included things like: 'Someone upset or hurt me' and 'I need a buddy for recess' and then each child's name in the class so they can point to the name. We also put things like 'I can't find my....' and then on the other side a list of things they might have lost. We also put more open ended things on there like 'I am worried about something' so then the teacher can try and draw out what the worry is, whether using a whisper buddy or writing it down or nodding if the teacher guesses correctly. We've also made cards for our daughter to use with her friends that say ' will you go with me to ask for help?' 'thank you' and 'please can I play with you at lunch?' 6. Whenever the child is finding the use of cards easy, make it a little bit harder e.g if the child is already verbal with the teacher when no one else is around, the teacher could take the child into a quiet corner and see if they can repeat one word that is on the card. You can use humour too. E.g. 'Saskia, I can see that you have a help card there. Let's go in the corner and see what it is. Oh, do you need to go to the toilet or do you need to tell me there is a hippo on the oval?' Saying just 'toilet' or 'yes' can then be heavily rewarded. Or even just sounding out the letter T for toilet. 7. Another way of making it harder is instead of responding to what the card says each time is to get the child to whisper what is on the card to a friend. Gradually over time the whispers get louder so the teacher can hear. I prefer not to use just a whisper buddy and no cards because if their buddy is away or they have had a falling out then they are stuck. They can also become too dependent on the buddy. With the cards they are initiating it themselves but can still use a friend for help too. 8. Make sure that the teacher doesn't spring new challenges on the child. It needs to be planned in advance. They might take a quiet moment and say: 'Nathan, you have been doing so well with using your cards all week. Do you think you would be brave enough next week if we go in the reading corner and you could sound out the first letter to me for 4 stickers on your reward chart?' If the child looks really stressed then find another challenge that they think they might be able to do. It could be something as small as sitting closer to the group on the mat instead of hiding away at the back. Or using the cards with a relief teacher. 9. Different children find different things hard. Some might find signs easier than cards, but for most children cards come first then signs, as signs are more expressive and there is also some performance anxiety about doing the sign 'wrong'. This is an old Facebook post which was one of my most popular ever, so I'm re-running it, but some of our circumstances have changed. I'll add those in a comment at the end.

Living with anxiety is exhausting, especially for young children who are already exhausted after a day at school anyway. The nature of SM means that children rarely show their feelings during the school day, so what is bottled up tends to come tumbling out when they get home. Dinner is always late in our house because it takes at least an hour and a half before I can even think about making dinner. Here are a few things that have helped us to cope with the inevitable after school meltdowns. Every child is different so they may not work for your family. I keep saying 'she' and 'her' instead of 'they' because my big one is now fine and transitions smoothly between school and home. My little one also has epilepsy which affects the quality of her sleep, so for her, even though she is over the worst of the SM, I still anticipate having these problems until she (hopefully) grows out of her epilepsy. * I've given up asking questions or making conversation in the car on the way home. My daughter prefers silence and if I talk to her before she has 'decompressed' it just causes arguments. The bad mood often then starts before we even get home! * Even though I'm desperate to know how her day went I usually save the questions until after dinner as she seems to have recovered by then. I also ask questions in a round about way so it's not obvious that I am anxious about her anxiety! * The first thing we do when we get in is sit down and snuggle together while she eats anything that is left in her lunch box. I usually put in more than she needs so that it is right there ready and then we don't have to wait for me to make a snack. * Protein & fat will stabilise blood sugar and mood after school much better than carbohydrates. * I make sure she's drunk all of her water from her water bottle and then refill. * Going to the toilet is not optional after school. I enforce a 5 minute sit at least. Then another one after dinner. This is because SM kids often won't poo at school, some won't even wee and/or have accidents. You don't need constipation as well as everything else. * I find that going in the bath before dinner seems to wake her up and snap her out of her funk. Mood can change instantly after a bath it seems. If she is having a meltdown where we can't even manage a cuddle & snack then it's straight into the bath and eat in the bath! *Once she is in her PJs, depending on mood - she might play outside or read or watch TV. If I'm expecting her to do any kind of chores like unpacking her bag, putting her shoes away, putting her school uniform in the wash basket and feeding the pets, then I don't allow any TV until those are done. * That takes us though to dinner, shortly followed by bed. * If we are having difficult behaviour even after getting into PJs then I might encourage a quiet time in her room listening to an audio book or meditation, more snuggling with me, more snacks or just ignoring her. * If things are really bad then I initiate a 'Code Blue' which is get ready for bed immediately upon coming home from school, scrambled egg or beans on toast for tea, a long story and wind down with Mum, then in bed by 6.30/45 pm * The only thing that has speeded up our evening routine is I have made a laminated list of after school jobs and I expect her to do all or some of it on the days when she is not too tired. Then I can get on with dinner sooner. More often than not she is too tired to do much. I know for most kids it's pretty basic to at least unpack your school bag but I don't worry too much if she doesn't do it, as long as she knows how to be independent on the good days. * Young kids with SM will probably be too anxious to be picked up at the gate (kiss n drop - or whatever it's called at your school) but if Yr 1s and above are able to work up to it, if you have a drive by pick up area at your school, then oddly this has worked really well for us. My little one is not anxious about it because her big sister picks up her up from her class and walks her over to the gate. I used to find that the walk from the classroom to the car (which is quite long and busy at our school) was the time when the worst meltdowns began. The heat (or rain), the crowds, the noise, the heavy bag and the chance to push back against Mum were just too much for her. Walking to the gate is way less stressful for her and she gets to decompress in the shade with her sister & friends for 15 minutes after school. Obviously as a parent of an SM child you can't do that every day as you want to keep an open line of communication with the teacher, but I find that only going in when I have a meeting reduces my frustration too at the amount of time I spend at school ( which is a lot with mornings, meetings and facilitating her support work). Hope that helps some people! Update: 02 May 2017 - after school behaviour is much improved in our house, but there are still bad days, weeks and months! Completion of the after school list is gradually improving. We now have a puppy and I try whenever possible to bring him on the school run with me. Having him sitting next to her in the car definitely lowers my daughter's anxiety / overwhelm before and after school. In the winter I find that it is waking up which is more problematic than after school. During terms 2 & 3 we get up half an hour earlier and the girls have their bath then. The bath is already run and the fire is on with their school uniform laid out in front of it before I wake them up. It's a much nicer way to ease into a winter morning and seems to reduce the amount of GET READY shouting from me! |

SUSANNAH BAdelaide Hills Postnatal Support Specialist CATEGORIES

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed